Researchers retracing the steps of a 1985 expedition in the Peruvian Andes have documented how the area's bird populations have shifted – and in some cases disappeared altogether – due to warming temperatures in the intervening 30 years.

"Mountaintop species are running out of mountain," explained zoologist Benjamin Freeman, lead author of the study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. "The next step is extinction. Of the 16 mountain-top species found in the 1985 survey, eight are missing from our new survey."

The researchers believe there is a high statistical probability that at least four species have been extirpated from the survey area, given the team's extensive field searches and analyses of audio recordings. The missing birds are Variable Antshrike, Buff-browed Foliage-gleaner, Hazel-fronted Pygmy-Tyrant and Fulvous-breasted Flatbill. Though none of these species is considered threatened and they are fairly widespread, this research supports the idea that birds living at higher altitudes are moving even higher in reaction to climate change, which can result in local extinctions.

Montane species, such as Variable Antshrike, are already suffering local extinctions in some areas of the Peruvian Andes as a direct result of global warming (Tim Dean).

Freeman led the resurvey of Cerro de Pantiacolla, a 1,415-metre ridge in southern Peru, covering the same ground and employing the same methods used in 1985. Cornell Lab of Ornithology director John W Fitzpatrick led the 1985 survey and co-authored the new report.

"This is the first field-work evidence to show that some local bird populations were literally wiped out by upslope shifting," summarised Fitzpatrick. "We think this pattern is probably being repeated on tropical mountain slopes all over the world."

"Since the 1985 survey, the annual average temperatures in the region have increased by around one degree Fahrenheit," Freeman added. As a result, he says that more than two-thirds of the species studied in the research have shifted their ranges upslope an average of 40 metres to stay within their habitat.

The work in Peru follows research by Freeman that found 70 per cent of bird species on a New Guinea mountain had shifted their ranges upslope, and his team’s global meta reviews of previous studies. With Earth's average temperatures predicted to warm as much as two Celsius by 2100, tropical species can be expected to shift upslope by another 500 to 900 metres.

"Tropical mountains harbour thousands of bird species, more than any other terrestrial environment on Earth," Freeman explained. "Minimising the effects of climate change on these birds means preserving and restoring forested wildlife corridors at all elevations. Otherwise, we’ll continue to lose mountain species at this very rapid rate."

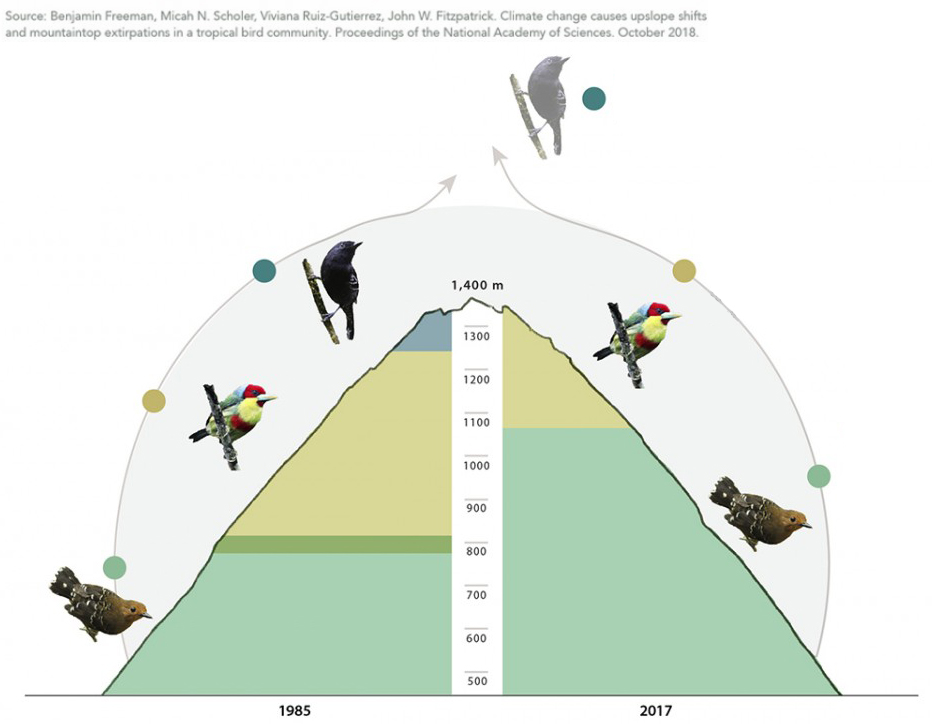

Above: Diagram illustration the upward altitudinal shift of three bird species from the study area. Common Scale-backed Antbird, a low-elevation species, has benefited from climatic warming, expanding upslope to occupy a 17 per cent larger area in 2017 than in 1975. However, the range of Veriscoloured Barbet has shrunk by two thirds and Variable Antshrike, which occupied the mountaintops in 1975, has disappeared from the region altogether. Adapted from Freeman et al.

No comments:

Post a Comment