A new study has given researchers around-the-clock insights into the behaviour of individual hummingbirds visiting feeding stations.

'Beep' is not a sound you expect to hear coming from a hummingbird feeder, yet beeps abounded during a study led by the University of California, Davis, to monitor hummingbirds around urban feeders and help answer questions about their behaviour and health.

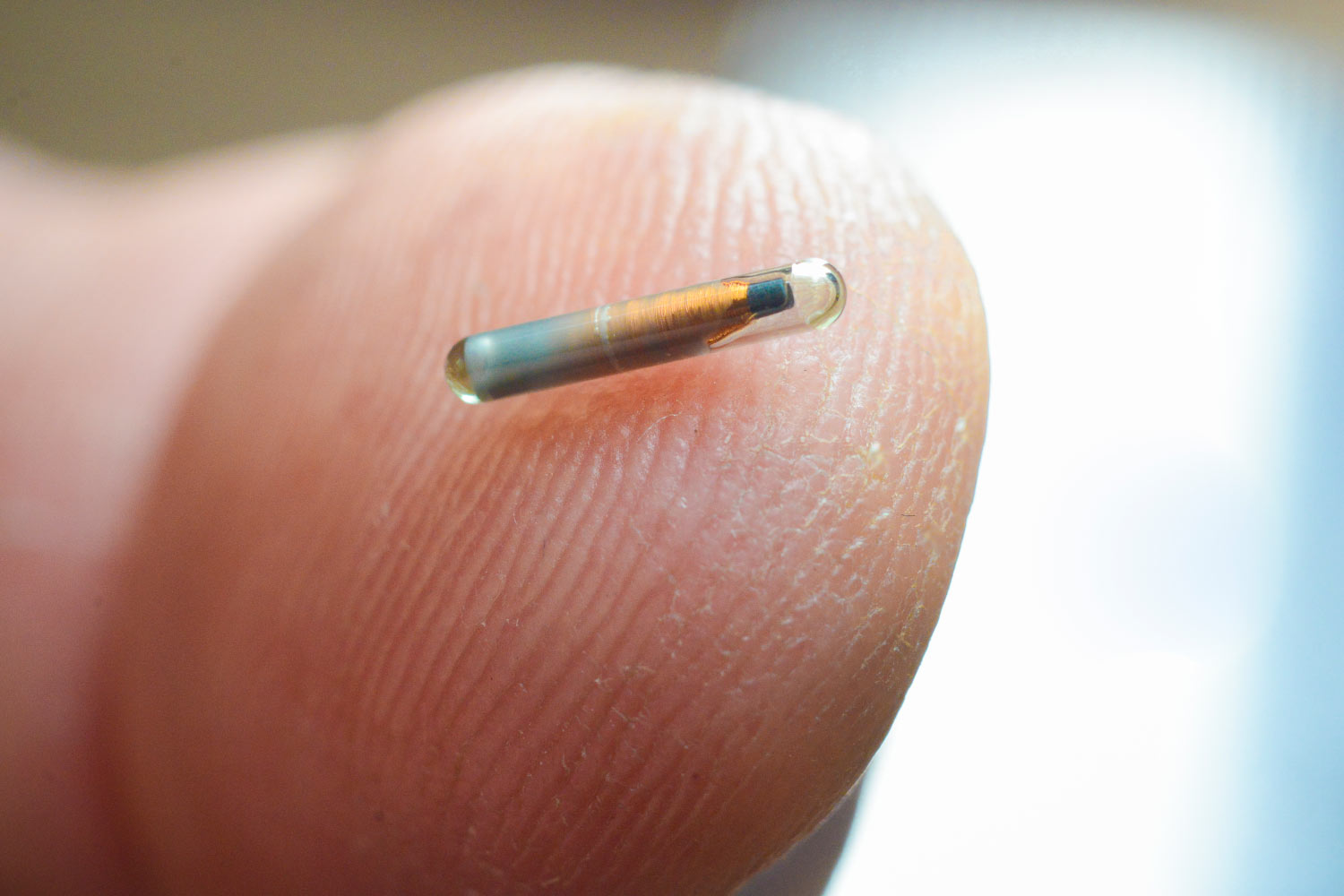

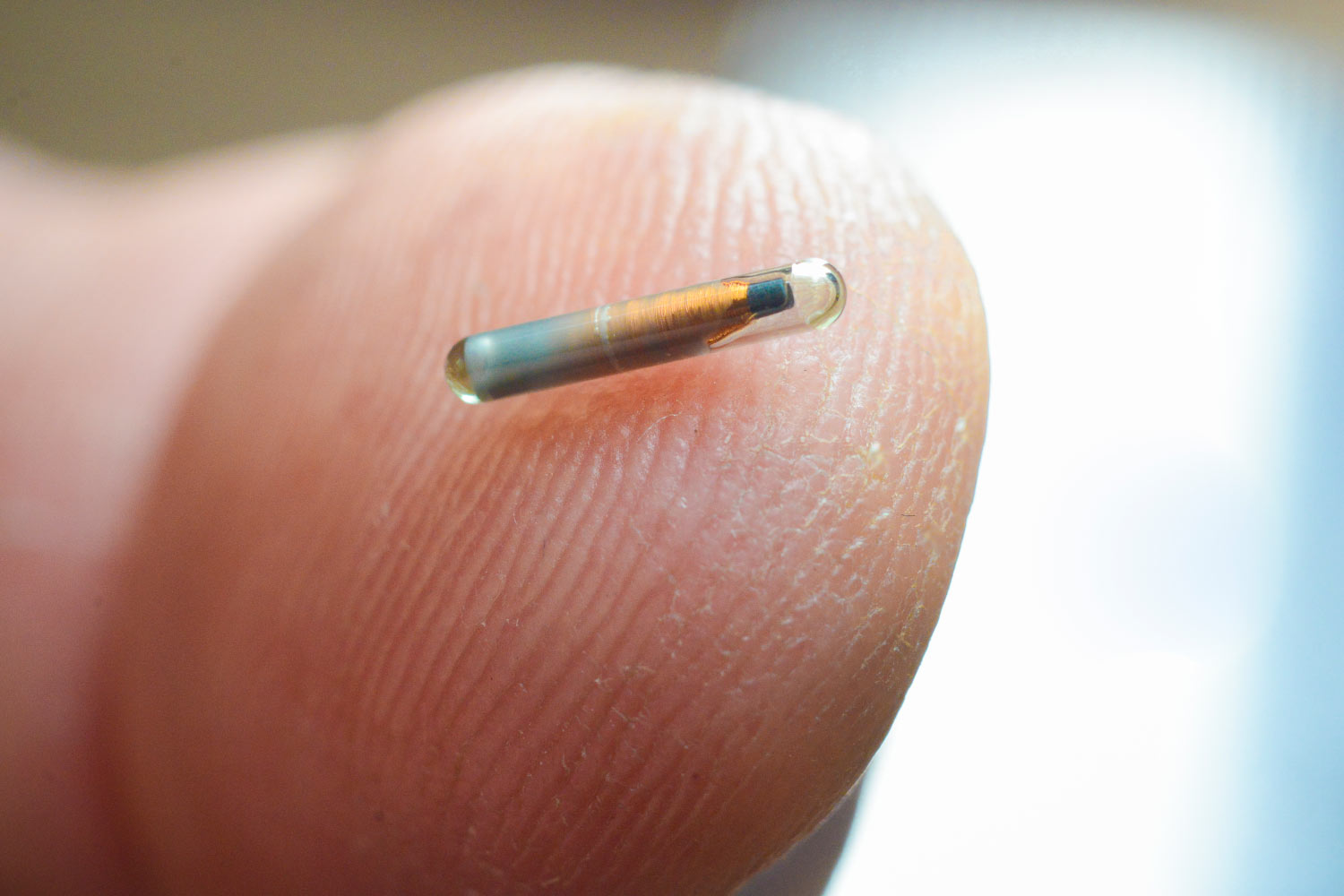

For the study, published recently in the journal PLOS ONE, veterinary researchers tagged 230 Anna's and Allen's Hummingbirds with passive integrated transponder (PIT) tags and recorded their visits to feeders equipped with radio-frequency identification (RFID) transceivers. This is the same technology that animal rescue shelters use when placing microchips under the skin of cats and dogs so they can be tracked if lost.

The study focused on the behaviour and number of visits of both Anna's (above) and Allen's Hummingbirds to feeding stations in California (Manfred Kusch).

The study focused on the behaviour and number of visits of both Anna's (above) and Allen's Hummingbirds to feeding stations in California (Manfred Kusch).

Similar to when a grocery item is swept across a supermarket scanner, little beeps sounded each time a hummingbird fluttered inside one of the study's feeding stations. This gave researchers around-the-clock information about how often individual hummingbirds visited the feeders and how long they stayed there.

Such information can help explain how hummingbirds interact with each other at feeders, as well as inform veterinarians about potential disease transmission that could occur from such interactions.

A passive integrated transponder tag, shown on a fingertip for scale, is inserted under the skin of a hummingbird to help researchers monitor its movements (Don Preisler/UC Davis).

A passive integrated transponder tag, shown on a fingertip for scale, is inserted under the skin of a hummingbird to help researchers monitor its movements (Don Preisler/UC Davis).

In the wild, hummingbird species do not tend to directly interact much with each other. But with urban feeders, that dynamic changes. "Hummingbird feeders attract birds to gather in areas where they normally wouldn't congregate," said co-leading author Lisa Tell, a professor at the UC Davis School of Veterinary Medicine. "This is a human-made issue, so we're looking at how that might change disease transmission and dynamics in populations."

RFID technology has been used to monitor hummingbirds before, but this is the first time it has been used to monitor multiple hummingbirds at feeders at the same time, which is critical when studying their interactions.

The study, conducted between September 2016 and March 2018, recorded about 65,500 visits to seven feeding stations across three California sites. These included the UC Davis Arboretum Nursery, a private home in Winters, west of Sacramento, and The Gottlieb Native Garden in Beverly Hills. More than 60 per cent of the tagged birds returned to feeders at least once — some immediately, some months later. During spring and summer, most visits occurred in the morning and evening hours.

Behavioural differences by gender were also recorded: females tended to stay longer at feeders than the males, while males overlapped their visits with other males more frequently than with other females.

"It's the first time we were able to truly quantify not only the time spent at feeders but also time spent co-mingling with fellow hummingbirds at these feeders," said co-leading author Pranav Sudhir Pandit of the UC Davis EpiCenter for Disease Dynamics within the School of Veterinary Medicine.

Science has yet to make an informed judgment call on whether backyard hummingbird feeders are 'good' or 'bad' for hummingbirds. The authors note that planting native plants known to attract hummingbirds, such as salvias and those with tubular-shaped flowers, provide a clear benefit to the birds. But given that urban hummingbird feeders are highly prevalent, researchers want to understand the health implications for birds congregating and sharing food resources at these bird buffets. Data from the study is one piece of that puzzle.

Science has yet to make a call on whether hummingbird feeders, like these in Beverley Hills, California, are 'good' or 'bad' for the birds (Jen May Photography).

Science has yet to make a call on whether hummingbird feeders, like these in Beverley Hills, California, are 'good' or 'bad' for the birds (Jen May Photography).

"The aggregation of hummingbirds in urban habitats due to feeders is the new normal and now it's time to understand the implications of this," said co-leading author Ruta Rajiv Bandivadekar, a visiting research scholar in the UC Davis School of Veterinary Medicine.

Before she was tagging hummingbirds, Bandivadekar was radio collaring tigers to monitor their movements at a national park in India. The collar itself weighed about 2 kg, whereas a hummingbird's entire body is about 5 grams.

Their small size is the main reason finding the proper technology to monitor hummingbirds can be challenging. For instance, before the study, researchers weren't sure they could successfully tag and monitor Allen's Hummingbirds, a smaller species the Audubon Society has determined to be a 'climate endangered' bird.

Regulations require that tracking devices weigh no more than 3 per cent of an animal's body weight, a maximum Tell and colleagues did not want to risk approaching. But the efficient use of PIT tags is providing valuable insight into their movements and behaviors, which could ultimately help their health and conservation in a changing landscape.