In a week in which October turned to November, there was enough excitement to reassure birders that this peculiar autumn still has some life in it yet. This was most acutely – and absurdly – illustrated by Friday evening's news of a Tengmalm's Owl at an undisclosed site somewhere in Orkney.

The associated photograph, of a rather surprised owl perched on a toilet seat, itself covered in detritus. The quantity of droppings suggested it had been there a while, but what would an exceptionally rare owl be doing in someone's toilet? The fact of the matter is that, at the moment, we don't really know much more about the circumstances of this bizarre occurrence, but presumably it will be written up somewhere in due course.

Orkney has a strong track record with Tengmalm's, with five of the seven accepted previous records since 1950 occurring on the islands, two of which were in spring, two in autumn and one in the depths of winter. As well as the legendary suppressed bird at Spurn, which was possibly present for months at the point there in early 1983, the species has a habit of proving untwitchable (either due to news being kept quiet or the individual birds perishing), and this latest record seemingly continues the unfortunate trend.

High-quality Siberian finds this week included a brief Dusky Thrush at Easington, East Yorks, early afternoon on 4th. Almost mythical in terms of its British status prior to the well-twitched Margate bird in May 2013, a further four individuals (including this week's bird) have since followed in just over five years. Another welcome discovery was a flyover Blyth's Pipit on St Mary's, Scilly, on 31st, which was later pinned down and showed intermittently to 4th.

Perhaps the stand-out record for the week, though, was a White-billed Diver in full breeding plumage off the north-east Kent coast. Found off Ramsgate during the late afternoon of 2nd, it spent the entirety of 3rd off Foreness Point before switching its favoured patch to the north-facing coast between Margate and Minnis Bay from 4-6th, often showing extremely well in the process. Any White-billed Diver is extremely rare in Kent, so to get a bird in near-immaculate breeding condition lingering and showing so well makes it a sure-fire highlight of the year for many local birders.

White-billed Diver, Foreness Point, Kent (Stephen Ray).

White-billed Diver, Foreness Point, Kent (Stephen Ray).

White-billed Diver, Margate, Kent (Steve Ashton).

White-billed Diver, Margate, Kent (Steve Ashton).

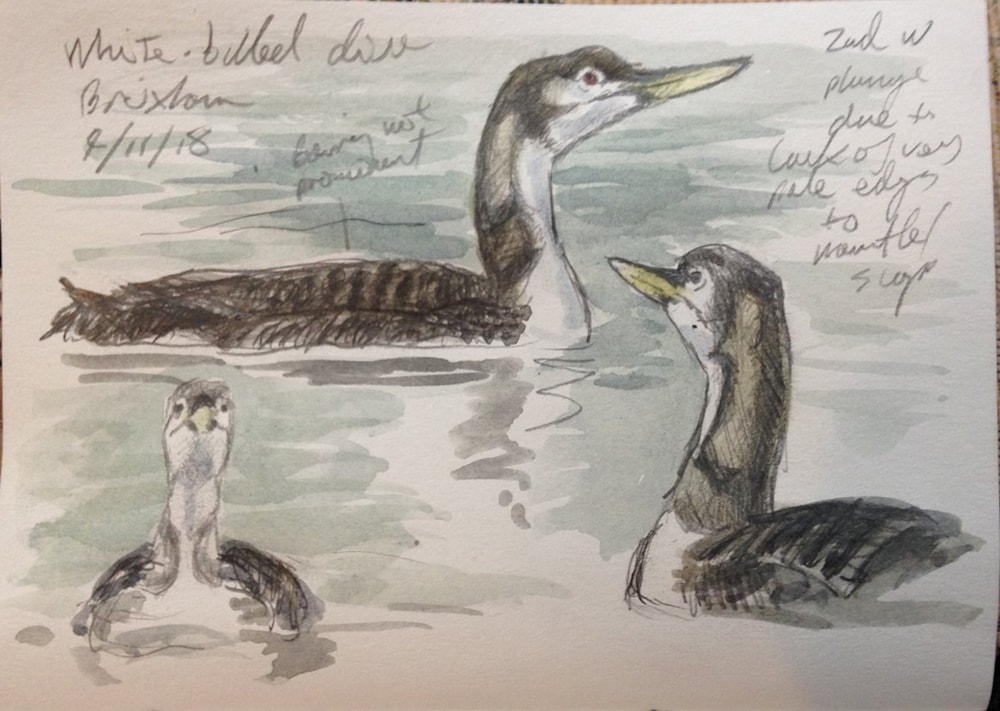

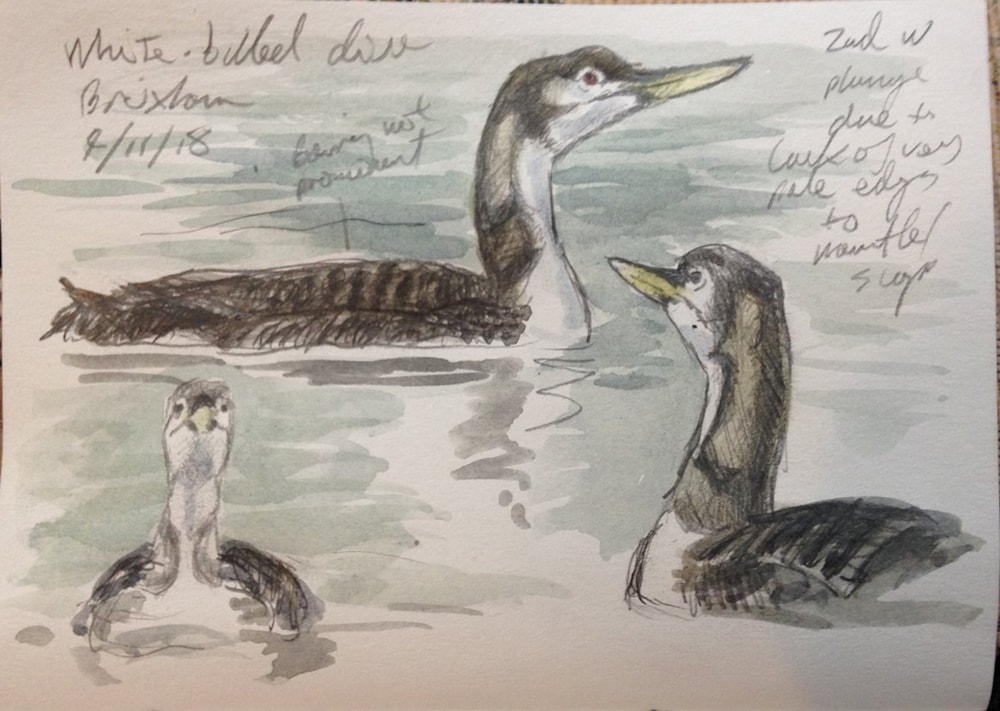

Another White-billed, this time in winter plumage, was discovered off Shoalstone Point, Brixham, Devon, on 4th – many birders will fondly remember seeing a confiding bird here in winter 2013/4, some of which enjoyed it on the same day as a Brünnich's Guillemot at Portland Harbour. Back to this week and further White-billeds were seen off Rubha Ardvule, South Uist, on 31st and both Lamba Ness, Unst, and Kirkabister, Shetland, on 2nd. Meanwhile, the Pied-billed Grebe was again noted at Loch Feorlin, Argyll, on 6th (the first report of it since August), and the Shetland bird remained at Loch of Spiggie.

White-billed Diver, Shoalstone Point, Devon (Mike Langman).

White-billed Diver, Shoalstone Point, Devon (Mike Langman).

A

Richardson's Cackling Goose was again reported from Oronsay, Argyll, on 31st. In Highland, two

Todd's Canada Goose were at Munlochy Bay on 5th, with the blue-morph

Snow Goose still there on 1st.

Black Brant were noted in Dorset and Norfolk. The

American White-winged Scoter was again noted off Musselburgh, Lothian, on 31-1st, while the

Black Scoter continued to show well off Cheswick Sands and Cocklawburn Beach, Northumberland, throughout, often in the company of just a handful of

Common Scoter. Musselburgh also bagged a

Surf Scoter; another flew past Bull Bay, Anglesey, on 31st and two drakes remained in St Andrews Bay, Fife. Norfolk's

King Eider remained stationary off Sheringham throughout. Five

American Wigeon included a new bird reported at Cottam, Notts, on 3-4th, but just four

Green-winged Teal were logged. Seven

Ring-necked Duck and the Anglesey

Lesser Scaup completed the wildfowl roll-call.

King Eider, Sheringham, Norfolk (Ian Bollen).

King Eider, Sheringham, Norfolk (Ian Bollen).

A Snowy Owl in the hills west of North Roe, Shetland, on 4th may well be the bird seen on Fetlar back in October. Meanwhile, in Orkney, the male was again seen on Eday.

It would be fair to say that a major invasion of Rough-legged Buzzards is underway, with no fewer than 40 sites logging the species. The influx was widespread, with birds reported as far north as Highland and Lothian, but also as far south-west as Dorset (Portland Bill on 31st) and Devon (Lundy on 1st). Typically, the east coast between Yorkshire and Kent bore the brunt of arrivals, with the Horsey area of Norfolk logging up to four individuals and two seen concurrently from Rainham Marshes, London, on 31st.

Rough-legged Buzzard, Dartford Marshes, Kent (Oscar Dewhurst).

Rough-legged Buzzard, Dartford Marshes, Kent (Oscar Dewhurst).

It would be reasonable to speculate that the juvenile White-tailed Eagle flying north over the Humber at Spurn, East Yorks, on 2nd and latterly seen at Holmpton and Flamborough Head (where it roosted) that afternoon is the bird seen in Norfolk last week. One wonders if it might be a Scottish bird, given it was still on its way north on 6th, having been relocated at Kildale, North Yorkshire.

A good showing of five Lesser Yellowlegs included new birds at The Midrips, East Sussex, on 3-4th and Tacumshin, Co Wexford, on 4-5th in addition to those still in Cornwall, Dorset and on Skye, Highland. The Baird's Sandpiper hung on at Goldcliff Pools, Gwent, to 3rd, while five White-rumped Sandpipers were split between two Irish sites: three were at Roe Estuary, Co Derry, on 4th and two lingered at Tacumshin. The only American Golden Plover was a juvenile still on Benbecula, Outer Hebrides, to 5th, while the sole Long-billed Dowitcher was again the adult at Frampton Marsh, Lincs. In Durham, the Spotted Sandpiperremained on show at Jarrow, Durham, throughout. The Cornish Temminck's Stint was last noted at Stithians Reservoir on 1st.

Lesser Yellowlegs, The Midrips, East Sussex (Richard Bonser).

Lesser Yellowlegs, The Midrips, East Sussex (Richard Bonser).

Spotted Sandpiper, Jarrow, Durham (Mark Fullerton).

Spotted Sandpiper, Jarrow, Durham (Mark Fullerton).

In Pembrokeshire, an adult Bonaparte's Gull was watched at Gann Estuary on 4-5th. A juvenile Kumlien's Gull was identified on North Ronaldsay, Orkney, on 4th. Just four sites noted Iceland Gulls; the adult in Troon harbour, Ayrshire, is presumably a returning bird. Glaucous Gulls were more numerous, with at least 15 noted, including a juvenile as far south as Weymouth, Dorset. Some 40 Caspian Gulls were seen, mainly across central and eastern parts of England, but with notable exceptions: a second-winter commuted between Marazion and Hayle Estuary, Cornwall, while a first-winter was a very significant find at Donnybrewer, Co Derry, on 4th.

Caspian Gull, Dungeness NNR, Kent (Richard Bonser).

Caspian Gull, Dungeness NNR, Kent (Richard Bonser).

In the mild conditions, it was no great surprise to see a series of late-season swifts make appearances in southern parts. Confirmed Pallid Swifts graced Skokholm, Pembs, and North Foreland, Kent, on 4th (the latter having roosted in nearby Margate overnight), with modern digital photography yet again proving its worth by enabling high-quality images to confirm identification. Prior to this, two presumed Pallids were over The Naze, Essex, on 1st and a Common/Pallid Swift had flown over Salthouse and Cley, Norfolk, on 3rd, with another briefly at Black Down, West Sussex, on 31st.

Pallid Swift, Skokholm, Pembrokeshire (Skokholm Warden).

Pallid Swift, Skokholm, Pembrokeshire (Skokholm Warden).

Further products of the southerly airflow were three Hoopoes. On 1st, birds were noted at Escrick, North Yorks, and Shaugh Prior, Devon, while another at Hilmarton, Wilts, on 5-6th had apparently been present for a few days prior to it first being reported.

It was almost a surprise that the conditions didn't produce a Desert Wheatear or two, but last week's female Pied Wheatear remained on Foula, Shetland, throughout and another, a male, was identified along the seafront at Meols, Cheshire, on 6th, by which point it had already been present two days – this was a very welcome county first. Meanwhile, in Norfolk, the Stejneger's Stonechat prolonged its already lengthy stay at Salthouse, Norfolk, by another seven days.

Pied Wheatear, Meols, Cheshire (Mark Woodhead).

Pied Wheatear, Meols, Cheshire (Mark Woodhead).

Stejneger's Stonechat, Salthouse, Norfolk (Tom Hines).

Stejneger's Stonechat, Salthouse, Norfolk (Tom Hines).

Another typical early November arrival was a Hume's Leaf Warbler at Durlston Country Park, Dorset, on 6th – the first in the country this autumn. A total of four Pallas's Warblers were seen, with arrivals at Beachy Head, East Sussex, and Landguard, Suffolk, on 5th both lingering into the following day and thus proving twitchable (others were seen in Kent and East Yorkshire). A total of five Dusky Warblers were seen, including one showing fairly well at The Naze, Essex, from 31-2nd, two on St Mary's, Scilly, and two found on 6th, in Dorset and Durham. Siberian Chiffchaffs were seen at 15 sites, while Yellow-browed Warblers remained quite numerous in the southern half of our isles.

An Isabelline Shrike performed well at Birling Gap, East Sussex, on 2nd, but couldn't be found there the following day, while there was a report of a Rustic Bunting at Kilnsea Wetlands, East Yorks, on 2nd. Four Little Buntings were seen, with birds in Co Cork, Scilly, Cornwall and East Yorkshire. After last week's influx, just three Coues's Arctic Redpolls were seen. In Norfolk, birds remained at Blakeney Point to 31st and Wells Woods to 2nd, while North Ronaldsay, Orkney, bagged one on 5th. On Unst, the Hornemann's Arctic Redpoll was still at Lamba Ness on 31st. Interestingly, a group of seven Parrot Crossbills was reported at Horsford, Norfolk, on 6th. Two European Serins graced St Mary's, Scilly, on 5th, while two Common Rosefinches were in the Outer Hebrides and a third was trapped and ringed at private site in East Sussex.

Isabelline Shrike, Birling Gap, East Sussex (Beachy Birder).

Isabelline Shrike, Birling Gap, East Sussex (Beachy Birder).

Yellow-browed Warbler, Easington, East Yorkshire (C Corbidge).

Yellow-browed Warbler, Easington, East Yorkshire (C Corbidge).

Three of the week's five Rosy Starlings were in Wales, with new birds near Llanelli, Carmarthen, and at Pen-y-Sarn, Anglesey, in addition to the lingering first-winter in Llandudno, Conwy. Others were noted in Cornwall and Somerset. Barred Warblers numbered around 10 and four Red-breasted Flycatchers were seen on 31st, although just one of these lingered into November (at Fife Ness), while 12 sites across England and Wales logged Great Grey Shrikes. Around a dozen Richard's Pipits included an inland flyover at Rawmarsh, South Yorks, on 31st. The Olive-backed Pipit was last seen on St Mary's, Scilly, on 4th.

Great Grey Shrike, Flamborough Head, East Yorkshire (andy hood).

Great Grey Shrike, Flamborough Head, East Yorkshire (andy hood).