Native to sub-Saharan Africa and Madagascar, Pied Crow is common and ubiquitous in urban areas as well as more open country. Although largely sedentary, some post-breeding movements have been noted in wet years.

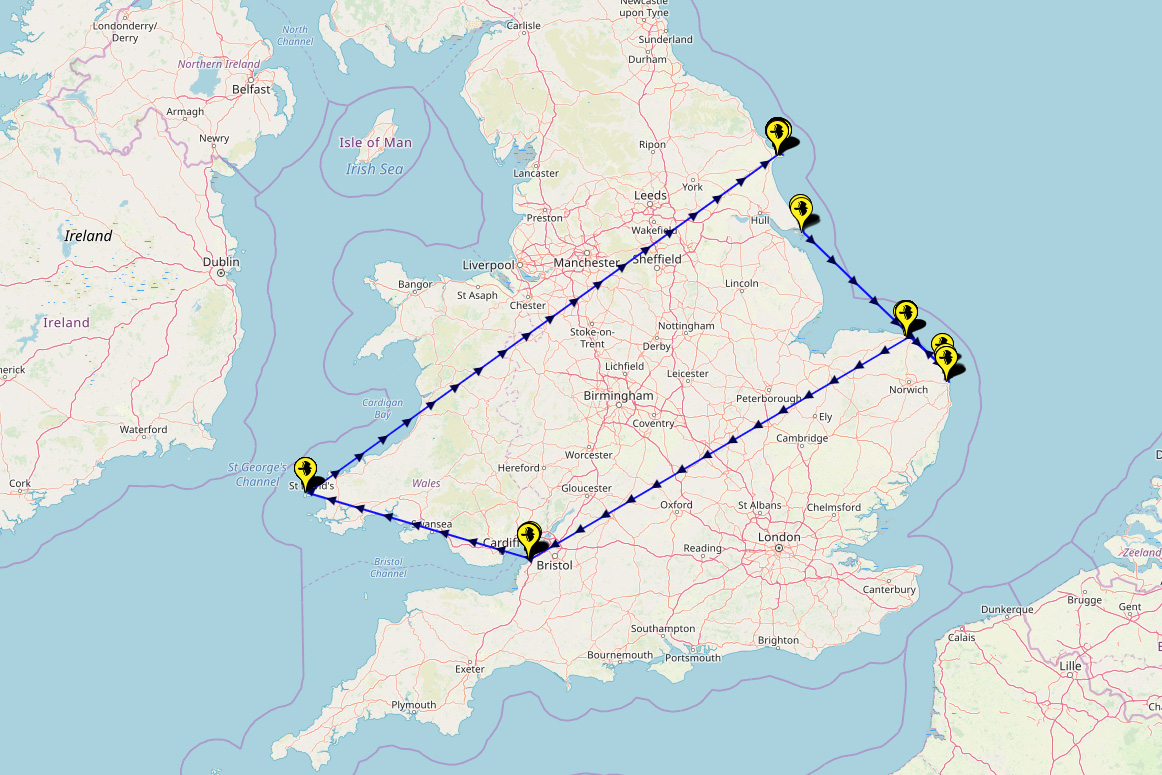

After one was seen heading south through the migration hot-spots of Spurn, East Yorks, and Gibraltar Point, Lincs, on 13 June 2018, it was subsequently relocated in the vicinity of the racecourse at Great Yarmouth, Norfolk, from 15-17th before reappearing around a Cromer chip shop on 19th. After doing a bunk on 23rd, it seemed sensible to assume that that was it for further sightings but, remarkably, it was relocated over 300 km away at Clevedon, Somerset, just three days later, where it inhabited the rooftops above the local Greggs for eight days.

The Pied Crow showed very well at Cromer, Norfolk, for several days in June, where it enjoyed eating discarded chips (Trevor Williams).

It subsequently popped up at a campsite near St Justinian, Pembs, from 3-8 July – a further westward movement of 180 km. Its tour of Britain wasn't complete there, though: extraordinarily it reappeared back in East Yorkshire on 24 July, when it was seen in Flamborough village, roughly 420 km from its last location. Seemingly now contented, it has subsequently remained there until at least mid-December, favouring the rooftops around Beech Avenue.

A chronological path of the Pied Crow's movements from June-December 2018 (BirdGuides.com data).

Breeding as far north as Mauritania, Niger and Sudan, Pied Crow has a chequered and controversial history within the Western Palearctic. A number of Moroccan, Algerian, Libyan and Egyptian records are seen as genuine, as are a pair seen on the Italian island of Lampedusa on 20 March 2018. These show a considerable northward movement of around 1,600 km from the species' usual range. Despite this, all seven Iberian records have been controversially assumed to either be escapes or ship-assisted – including birds seen crossing the Strait of Gibraltar. The species has even bred in the region, with an active nest found in Western Sahara in 2010, and a long-staying individual in A Coruña, Spain, paired with a Carrion Crow in 2006-07.

There are currently up three birds in residence near Puerto de la Luz on Gran Canaria, which arrived on a mobile oil rig that had been moored off the Mauritanian coast. In 2002, one appeared on a longline fishing vessel over 160 km out to sea between Western Sahara and the Canary Islands; that year, several on Gran Canaria were traced back to a Russian fishing vessel. Several sightings in The Netherlands are also suspected to have involved ship-assisted birds.

Outside the Western Palearctic, a vagrant was recorded from the Yemeni island of Socotra in 2003-04, and a record from India in autumn 2017 is still under consideration – but is considered to be likely ship-assisted. Additionally, there eight records from around Port of Santos, near São Paulo, Brazil, all of which are assumed to have been ship-assisted.

The 2018 Pied Crow, here photographed in Clevedon, Somerset, showed a distinctive peachy wash to its plumage when it first arrived. Was it the result of being sandblasted somewhere in the Sahara, or is that wishful thinking? (Mike Trew).

It is also a species commonly kept in captivity. One such bird kept at Knaresborough Castle, North Yorks, went viral on social media in July for its astounding mimicry of a Yorkshire accent proclaiming "Y'alright, love!"

Several previous British records have been successfully traced back to their owners, including a singleton at Start Point, Devon, in 2006 that had escaped from a nearby aviary. The last Yorkshire record, a bird that appeared at Flamborough on 8 May 1999 before working its way south though Spurn, attracted a similar attention from would-be twitchers for a while. However, interest abruptly ended when another turned up in Derbyshire on 26 May and it was established that two had recently escaped from a wildlife rescue centre in Nottinghamshire.

Over six months on from the first sighting, the origins of the 2018 bird are still clearly up in the air. Showing no obvious signs of plumage wear, and slight peachy feather discolouration when it first appeared consistent with sand-blasting in the Sahara (or further south), it seems worthy of consideration as a ship-assisted or even migrant bird, despite the high escape risk. That said, its confiding nature suggests past affiliation with humans, and it seems unlikely that this long-staying and widely wandering bird will get anywhere near the British list. However, this bird's presence has been widely discussed both in literature and online, and it's arguably surprising that an owner hasn't yet come forward to claim it. Perhaps its origins don't lie in Britain after all ...

No comments:

Post a Comment