Saturday, 30 June 2018

Wednesday, 27 June 2018

Osprey Leadership Foundation launched

A blast from the horn of the Rutland Belle, as she set sail at Rutland Water last week, marked the official launch of the Osprey Leadership Foundation – a trans-border conservation initiative conceived by Tim Mackrill as long ago as 2011.

More than 60 people on board, at this most apt venue, were treated to the sight of at least two different fishing Western Ospreys, while Tim ran through the establishment of the foundation, its aims and its objectives.

The Rutland Belle gave attendees the chance to enjoy fantastic views of fishing Western Ospreys (Mike Alibone).

Tim Mackrill is best known for having led the Rutland Osprey Project for more than a decade. Having begun as a schoolboy volunteer, he was appointed Project Officer in 2006 before completing a PhD on the complexities of Osprey migration in 2016. During this period, he wrote The Rutland Water Ospreys (Bloomsbury 2013) and is currently compiling two new osprey titles for Bloomsbury, including a full-length monograph in the Poyser series.

Tim has travelled extensively in Europe and Africa, building relationships along the osprey migration flyway, particularly in the West African country of The Gambia, in the heart of the species’ winter quarters. Here he forged links with schools and, along with local bird guide Junkung Jadama, embarked upon an ambitious education program, visiting schools to fuel interest in conservation and ultimately linking Gambian school students with those in Rutland, communicating via Skype.

Among volunteers involved at the UK end of the education program, and also on board the Rutland Belle, was Ken Davies, who taught in a Peterborough school for 36 years and has been associated with the Rutland Osprey project for 10 years. Ken is a member of the project’s education team and has written three osprey ‘storybooks’ for young people to spark interest in osprey conservation.

Tim Mackrill introduces the Osprey Leadership Foundation aboard the Rutland Belle on 20 June (Mike Alibone).

Described as a grass roots project which is international in its scope, it is intended that the foundation’s education program in time will widen to include other countries on the flyway. In order for conservation to be successful, the whole flyway needs to be considered – not simply Rutland and the UK, but the migration route and wintering areas as well. It relies on having people on the ground who are passionate.

Therefore, under the osprey conservation umbrella, the scheme is set to operate at three key levels. Initially raising awareness and creating interest in wildlife, before setting up future conservation leaders in both the UK and The Gambia over three years, with young people in both countries participating in workshops, leading to reciprocal country visits. Finally, young people will be supported by offering bursaries to send them to university in the Gambia and Senegal.

The Osprey Leadership Foundation is a registered charity which relies on fundraising and donations. With this in mind, an onboard raffle of osprey-related prizes, with a top prize of a pair of tickets to the osprey photographic hide at River Gwash Trout Farm (worth £150), raised more than £400 for the foundation.

Further information about the foundation can be found at www.ospreylf.org and Tim Mackrill can be contacted directly at tim@ospreylf.org.

Threatened nightingale site confirmed as Britain's best

The dramatic decline of Britain's Common Nightingale populations – more than 90 per cent of these iconic birds have been lost in the last 50 years – has led to the species being placed on the Birds of Conservation Concern Red List. But the number of birds present has, until now, remained unknown despite this knowledge being essential for assessing the importance of individual sites occupied by the species.

The latest figures from the British Trust for Ornithology (BTO) have recently been published; they used state-of-the art methods for assessing the size of national bird populations.

A team lead by Dr Chris Hewson at the BTO, and relying on thousands of hours of volunteer surveying, employed several analytical methods to produce the most robust population estimate possible. Dr Hewson estimates that the number of singing males is between 5,095-5,983 individuals, distributed at sites spread across the south and east of England. Moreover, the importance of Lodge Hill, Kent, which is threatened with development following a series of planning applications, was highlighted. The results confirm that the site holds more than 1 per cent of the UK population, making it of national importance.

Dr Hewson commented: “Understanding how many nightingales we have left is vitally important if we are to save the species here in the UK, as it enables us to assess which sites are nationally important. The relevant bodies can then look into protecting those sites that exceed critical thresholds of importance, hopefully ensuring that future generations can hear the beautiful song of the nightingale for themselves.”

In 1999 the UK Common Nightingale population was estimated at 6,700 singing males, but this was likely to have been a significant underestimate due to the methods used. The new study highlights the importance of accounting for birds missed during surveys and accurately scaling-up to include birds outside of surveyed areas when creating national population estimates. The importance of using multiple methods to allow the robustness of population estimates to be assessed was also emphasised, especially when the results have implications for site protection and subsequent planning decisions.

This research was made possible thanks to the support of Common Nightingale survey volunteers across the country, donations from the public, grants from charitable trusts and from Anglian Water, who have championed the BTO's work with the species for many years. If you would like to help the charity with its continuing research you can donate via www.bto.org/donate.

Rarity finders: American Royal Tern in West Sussex

Living just 45 minutes away from Pagham Harbour and the Selsey peninsula, I’ve been a regular visitor for more than 30 years, seeing some very good birds but nothing to quite match what was to unfold on the afternoon of 19 June.

I’d spent the day birding nearby Medmerry and a couple of other sites in the area and had planned to finish up at Church Norton mid-afternoon to catch the last hour or two of the rising tide and watch the activity in the tern colony (in particular the Little Terns). I arrived a little late at 3.25 pm, with most of the harbour already flooded, leaving just a couple of diminishing muddy islands between me and ‘Tern Island’ out in the harbour.

As I sat down I could see some terns preening on the remaining mud. Without bothering to check through my bins, I trained my scope straight on them. I was astonished to see a large tern with a massive orange bill standing among the Sandwich Terns, positively dwarfing them.

My first thought was it must be last year’s Elegant Tern returning, knowing that it was almost exactly a year since that bird had been present in the Tern Island colony for around 10 days. I rattled off a few record shots on my bridge camera and then spent a few moments watching the bird. I noticed that it had a metal ring on its lower right leg and judged the bird to be at least half as big again as the Sandwich Terns. It sported a large black crown with a shaggy crest at the back of its heavy-looking head, and there was a prominent area of white around the base of the bill up towards the eye. The bill was large and very robust, bright orange with a rather deep base. It had dark legs, proportionately longer than the Sandwich Terns, making it stand much taller.

While I watched, it flew, showing pale grey wings and upperparts, and a white rump and tail. There were smudges of darker grey around the primaries, with the whole appearing almost white in the bright sunshine compared to the other terns and gulls. It circled the colony a couple of times, then flew eastwards across the harbour and eventually out of view.

With no other birders about I decided I needed to put out the news (including to the excellent local Selsey Birder blog). Having no experience of orange-billed terns (other than that Elegant), I hadn’t conclusively identified it, but it seemed odds on that it was a returning bird; it seemed to me that it would have been too much of a coincidence for it not to be. I plumped for Elegant Tern and put the news out; in retrospect I should perhaps have qualified it as probable or possible.

At this point, I had completely forgotten that last year’s ‘ET’ was colour ringed, while this bird just had a single metal ring on its lower right leg.

The bird flew back to the last remaining patch of mud between me and Tern Island. Phew! I’d been in a bit of a panic in case I was going to be the only one to see it. Only a moment or two after refinding it, the whole colony and all the birds on the mud went up in a ‘dread’; when they all settled down again, the large shaggy head and huge orange bill could be seen among the Sandwich Terns and gulls behind the new electric fence on the island.

This is where it stayed for the next two hours, apart from one brief fly around – looking very comfortable in the same spot in the colony that the Elegant Tern had frequented in 2017, further suggesting it was the same bird.

Around 100 lucky twitchers saw the bird at Church Norton at dawn the following morning, but many arrived just minutes too late to see it (Ian Lycett).

A steady trickle of birders was now arriving, including Bart Ives and Andrew House from the Selsey Birder blog. The tern was looking very settled in the colony, but now showing mostly just glimpses of its head, bill and neck behind the other birds. Andrew did raise the possibility of it being something other than the returning ET, but most seemed to agree it was most likely the same bird.

Having been watching for three hours, and with the tide still high, I left at about 6.30 pm, with new birders arriving all the time. I got home around an hour later to discover that the bird had been reidentified by the BirdGuides team as the second-summer American Royal Tern that had been frequenting the Channel Islands and northern France, a fact confirmed by its metal ring.

It was then that I checked records and photos of the ET and remembered that it was colour ringed, excluding the possibility of that bird. I checked my field guides and came to the conclusion that the bird I’d found was indeed an American Royal Tern, the clincher for me being the huge, robust bill, (much heavier than Elegant). A lifer for me, and a first for Sussex. Fantastic – what a fabulous bird!

The bird remained in the colony all evening and was seen by around 100 observers. It was still present the following morning at first light, though it apparently flew out to sea almost immediately, not to be seen again. It was relocated offshore around Weymouth, Dorset, later that evening.

I was disappointed to have misidentified this bird, but the experience has taught me to never make assumptions in birding, no matter how likely they might seem.

Friday, 15 June 2018

Counting songs: estimating the UK’s Nightingale population

Large-scale population estimates of species are used for several reasons, including the assessment and protection of important sites. However, determining a national population requires extensive surveying and using methods that allow counts to be scaled up to the number of birds actually present and across a larger area.

This new BTO study looks at different methods used to estimate the population of Nightingales in the UK. Nightingales have declined by 61% in the last 25 years and therefore determining which sites contain the largest populations is vital. The study focused on 2733 2x2 km squares, 2356 where Nightingales were known to be, as well as randomly-chosen squares whose selection was stratified based on habitat suitability. By using different analytical methods, the final population was estimated to be between 5094 and 5938 territorial males, of which only 55-65% were counted during the surveys. It is therefore important to consider how to fully control for variability in detection and for birds outside of surveyed areas when estimating national populations.

The study also highlighted the importance of Lodge Hill SSSI for breeding Nightingales, which was designated for its nationally important population of the species, based on the results presented in this paper.

Tracking Cuckoos to Africa... and back again

We've been busy over the past few weeks catching and tagging ten more Cuckoos and they are already on the move! Knepp and Lambert, caught on the Knepp Estate in Sussex, have both crossed the English Channel and are now in France. Bowie, aptly named by Chris Packham, and Cameron, both from the New Forest, and Thomas from Thetford Forest have also made it to France. The 2018 class of Cuckoos were all caught at breeding grounds in the south and Midlands of England and we hope they will help us understand more about why the Cuckoo population in these parts of the UK is faring so badly. We need sponsors for all our new birds so visit the website to choose your favourite. You can also help us by forwarding this email to interested friends and family members and encouraging them to sponsor a bird.

Wednesday, 13 June 2018

Speculation and the importance of data

We're concerned when it's cold – kicking up the snow to reveal the soil below for the hungry-looking European Robin during a walk in late February, and thinking about Cetti's Warblers, European Stonechats and Eurasian Wrens in the weeks and months that follow. We eagerly await the arrival of migrant species – predicting what will be back 'on patch' at the weekend and remarking on anything out of the 'norm'. We can't help it – it's these questions that keep birding so fascinating! So far, 2018 has provided us with lots to talk about, but is there cause for concern?

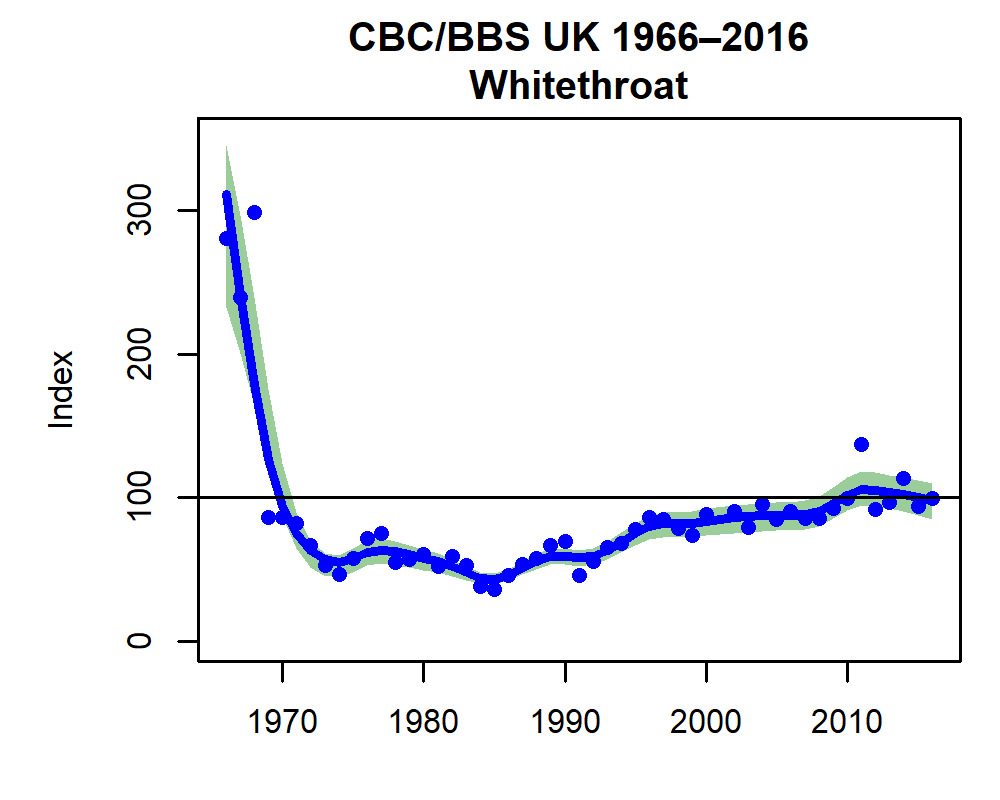

Social media would suggest that Common Whitethroat is enduring a very poor year so far in 2018 (Peter Blanchard).

The BirdTrack reporting rate graphs are certainly keeping many of us interested here at the British Trust for Ornithology (BTO) HQ – comparing hearsay with the graphs to see if this year's records are on par with the historic reporting rate. Do the numbers look below average? Did migrants return late?

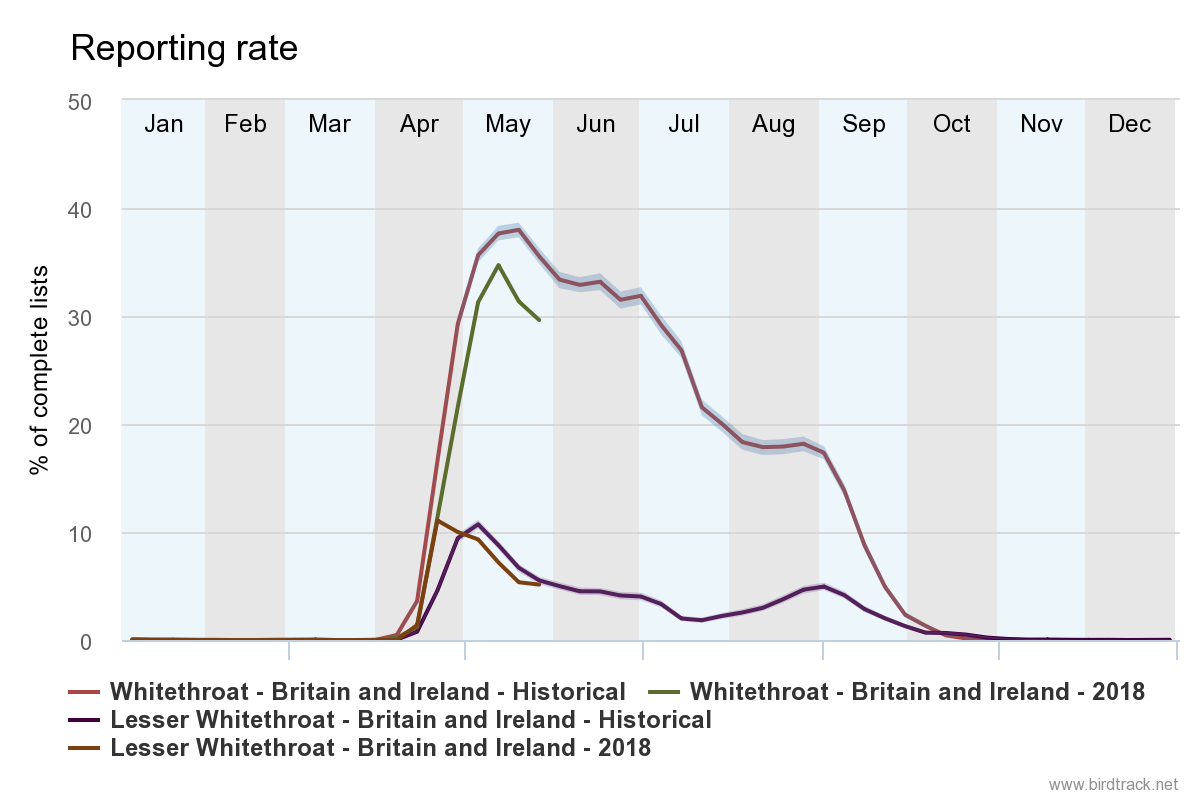

Here in south-east England at least, it felt as though Common Whitethroats were pipped to the post by Lesser Whitethroats. A quick glance at the BirdTrack reporting rate for England shows that the two arrived around the same time, but Lesser returned with a vengeance, whereas Common is below the historic average in terms of reporting rate. Might this change, though? It's possible that Common Whitethroats are still filtering in quietly and getting on with the business of nesting, meaning they are less detectable by song. Lesser Whitethroats could be settling down to breed earlier, with reports decreasing as a result in recent weeks – the peak looked on average, but the whole pattern looks a week or so earlier than 'normal'.

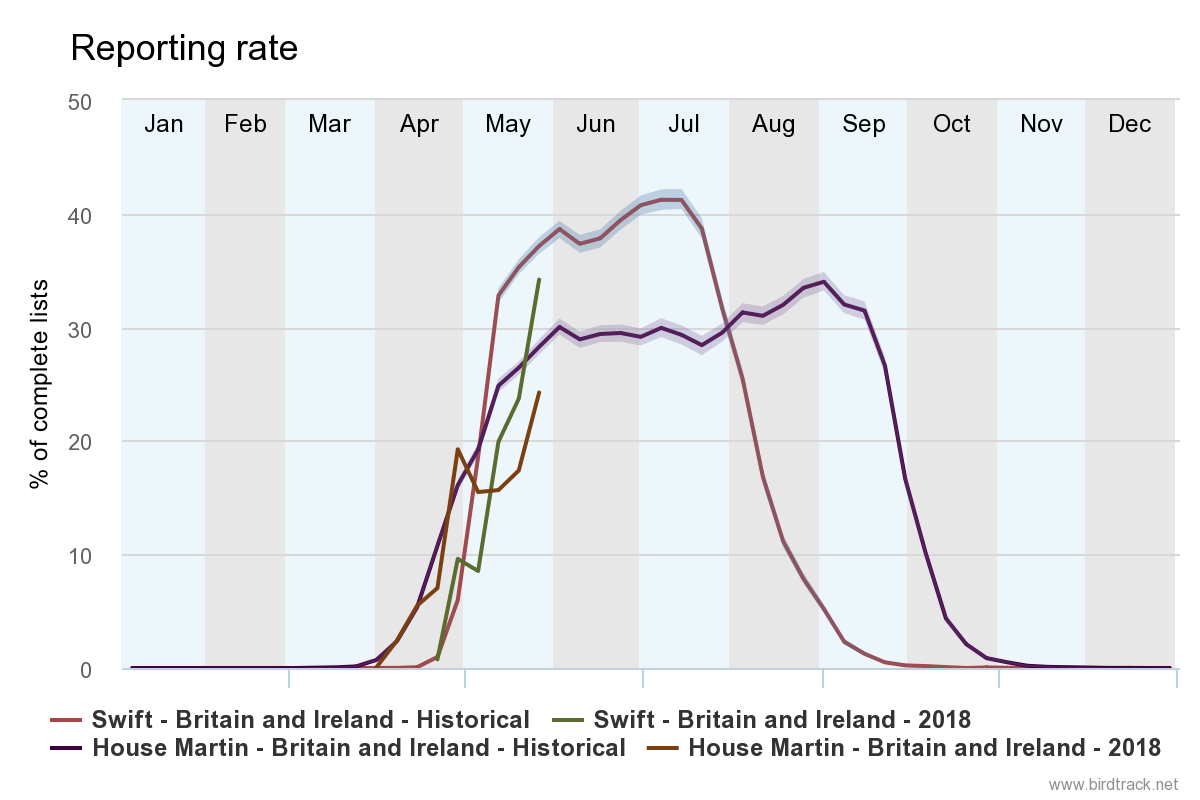

The consensus on social media is that House Martins and Common Swifts are back, but in much lower numbers than previous years. Is this reflected in data collected using complete lists in BirdTrack? On the latest UK-wide House Martin graph from BirdTrack all looked to be going fine, but the last fortnight shows the reporting rate to be well down on the historic average. Is swift late or down on previous years? Only the data can reveal this.

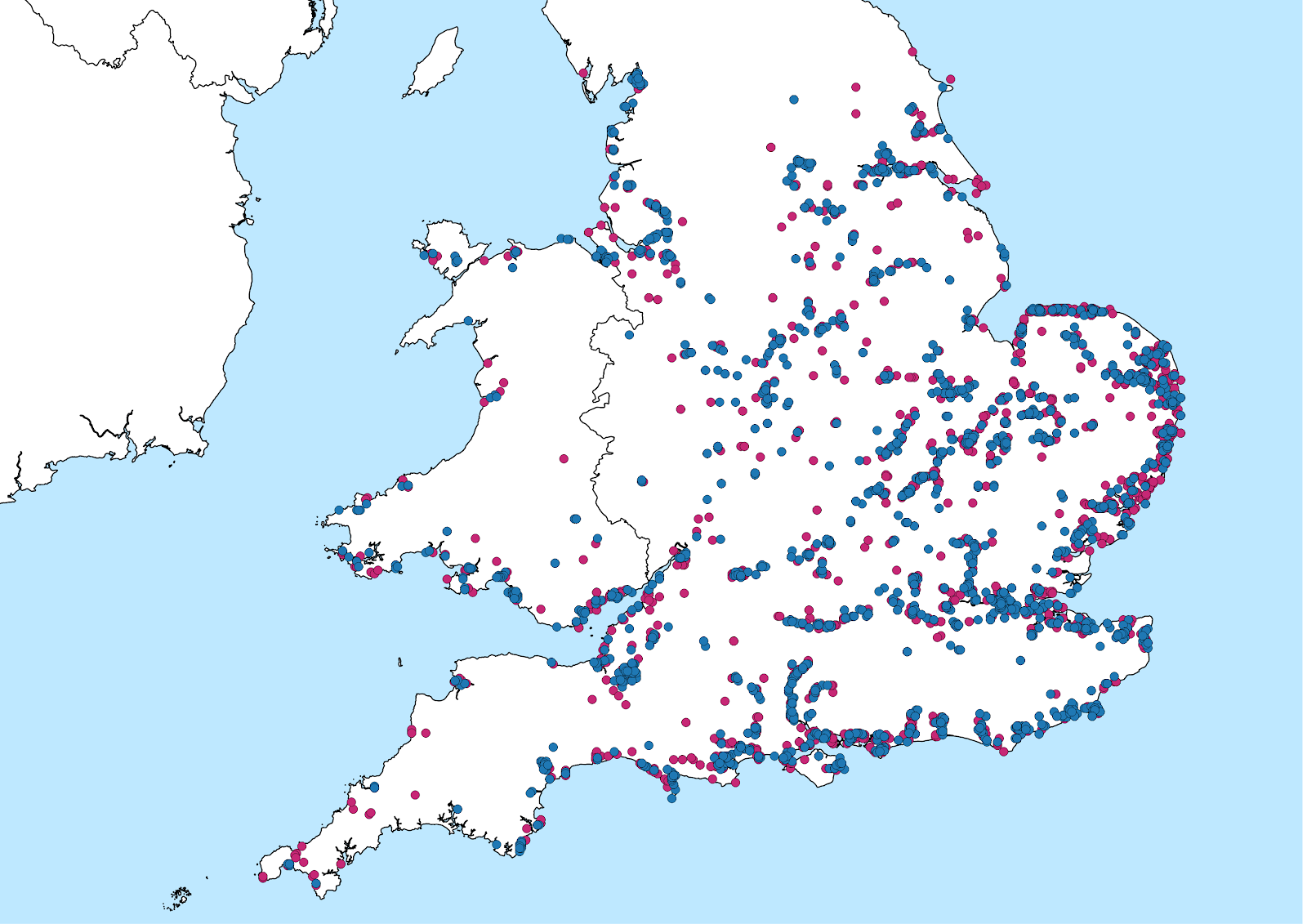

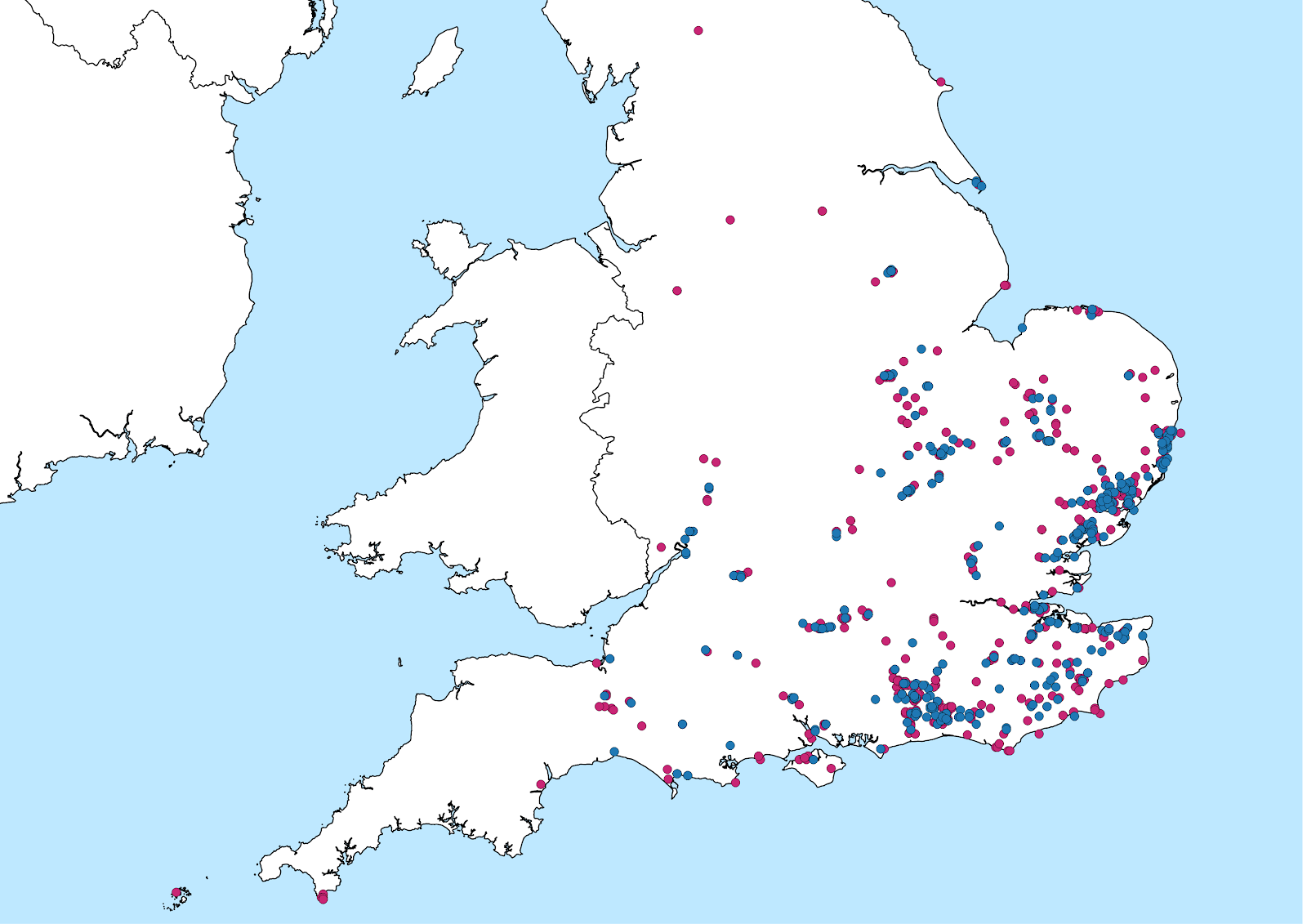

With a UK decline of 59 per cent revealed by the BTO/JNCC/RSPB Breeding Bird Survey (BBS), over the last 21 years, Common Nightingale is often at the fore of people's minds in spring, especially for birders lucky enough to have a local breeding pair. The distribution map of BirdTrack records for 2018 (blue) so far illustrate regional variation from 2017 (pink), with birds not being reported as far north and west as in 2017, and several sites reporting a decline in numbers or even a total absence.

Distribution map for Common Nightingales in 2018 (blue) compared to 2017 (pink).

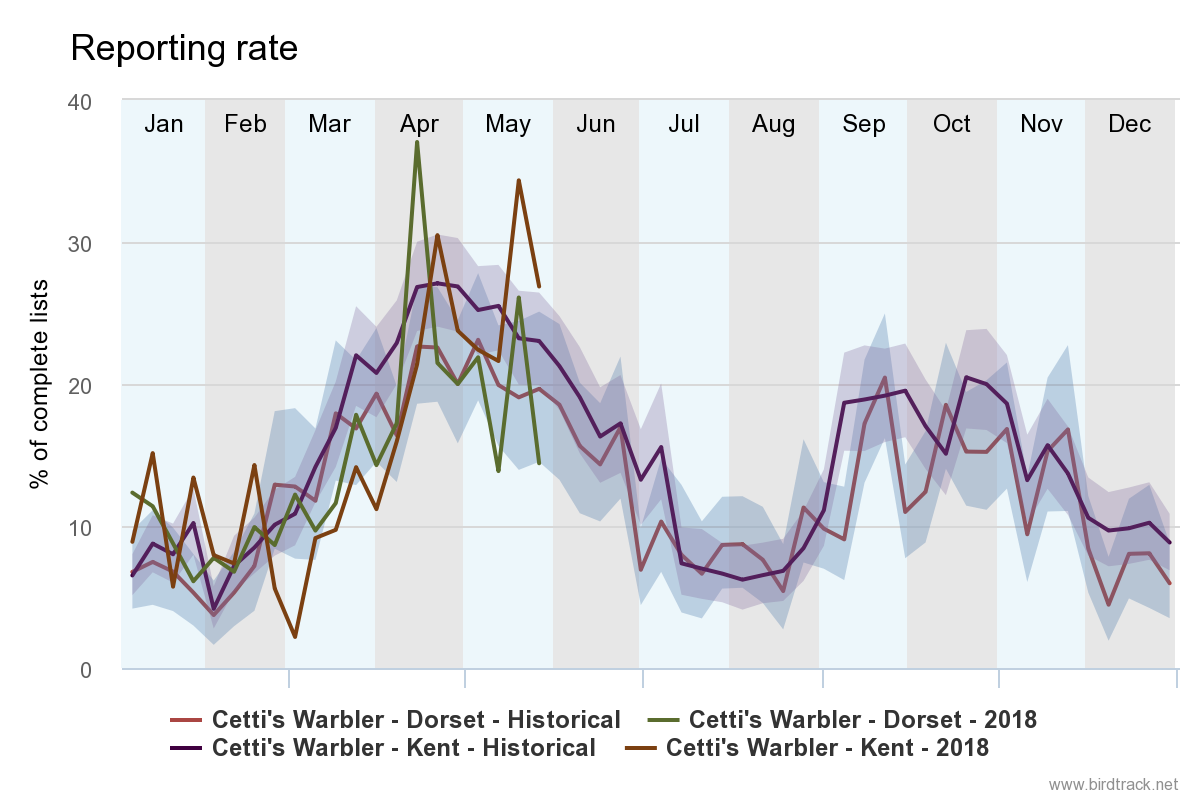

Continuing the theme of localised variation, BirdTrack data for some of our resident birds suggest the so-called 'Beast from the East' may have had more of an impact in some areas than others. A BirdTrack distribution map for Cetti's Warbler records covering 2017 (pink) and 2018 (blue) indicate that there has not been a significant reduction in distribution as a result of the cold weather. The reporting rate graphs, however, suggest that abundance in some areas has been affected. For example, Kent shows a significant drop in the reporting rate in late February and March, with reports slowly increasing back toward the historical average in April. The reporting rate from Dorset for the same period doesn't show a large drop in reporting rate around the time the cold weather gripped the UK – could a difference of just a day or two of harsh weather have influenced the resulting reporting rates for some of our resident species?

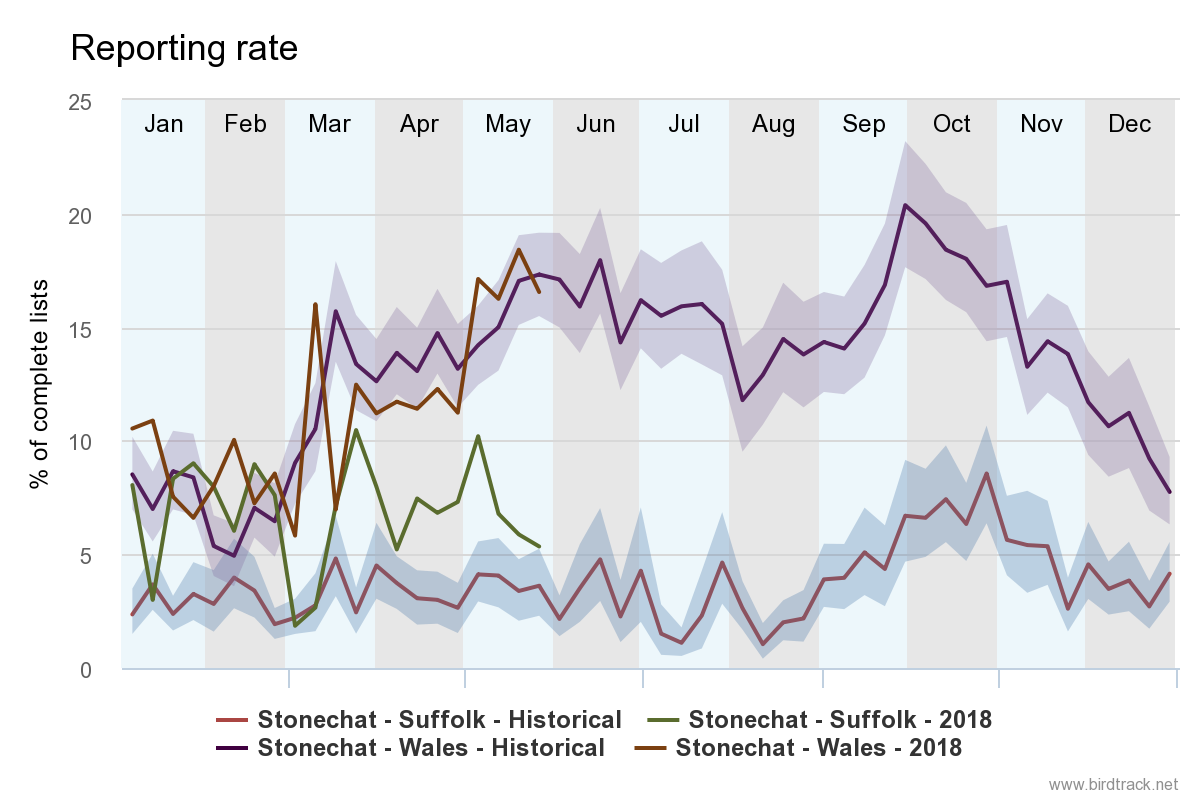

European Stonechats show a similar reduction in reporting rate in the east of England as Cetti's Warbler but, interestingly, after a couple of weeks of low reporting, bounced back and returned to levels above the historical average. Stonechats in Wales look to have been less affected by the freezing conditions brought on by the harsh weather.

All in all, early signs are concerning for some species, but there is only one way to find out how both our commoner resident and migrant species have fared between 2017 and 2018: the Breeding Bird Survey (BBS) results. Published a couple of months earlier in 2018 than previously, it is hoped the 2017-18 year-on-year trends will be released in early 2019, once data have been entered for the current year, checked and trends calculated (which takes more than a month to do!). These should provide some interesting reading.

BirdTrack is a fantastic (and addictive) early warning system but requires further manipulation and additional data from which to draw conclusions. However, the BBS produces trends for 117 common bird species, and as of 2017, this includes five- and 10-year trends, along with the all-time (21-year) trends, where sample size allows. These shorter-term trends have resulted in the sample size for Cetti's Warbler reaching the reporting threshold and with particular relevance here, a year-on-year trend which we will be racing to see when the 2018 BBS report is published. For now, do take a read of the recently published 2017 BBS report, available online at www.bto.org/bbs-report.

A good example of what BBS or rather its predecessor the Common Birds Census, can show us comes from way back during the winter of 1968-69, when the UK's Common Whitethroat population plummeted by 70 per cent. Research linked this crash to drought in the species' wintering grounds in the western Sahel, just south of the Sahara. What will the 2018 BBS report tell us about the 2017-18 winter for both resident and migrant birds?

Despite the hints from BirdTrack, feelings from birders in the field and trends from BBS, the results won't tell us why some species did well over winter and others did not – we can only leave that to further speculation!

So far this spring, the BirdTrack report rate of House Martin has been well down on previous years (Steve Hatch).

The importance of data

The above illustrates the importance of data collection, both via BirdTrack and BBS – not just for seeing changes in reporting rates and trends, but also for associated research, often examining the 'whys' and 'whens' behind population changes. This& is only possible when we have this kind of data stockpiled.

Here are some ways you can get involved.

BirdTrack: the scheme relies on your lists: simply make a note of the birds you see or hear, either out birding or from the office or garden, for example, and enter your observations on a simple-to-use web page or via the free app for iPhone and Android devices. BirdTrack records migration timings and distributions of birds throughout Britain and Ireland, as well as globally, and your records can be submitted year-round and from any country. For those new to birding, it is possible to contribute records of species you are 100 per cent confident in the identification of as casual records, and as your birding progresses or as experienced birders, you can enter 'Complete Lists' whereby every single bird seen or heard during a birding trip is submitted. Complete Lists are particularly useful because the proportion of lists with a given species provides a good measure of frequency of occurrence that can be used for population monitoring, as seen in the graphs in this article. You can add other valuable information like breeding evidence too, which is particularly helpful for county bird recorders and the Rare Breeding Birds Panel. BirdTrack provides facilities for observers to store and manage their own personal records as well as using these to support species conservation at local, regional, national and international scales.

BirdTrack is a partnership between the BTO, the RSPB, Birdwatch Ireland, the Scottish Ornithologists' Club and the Welsh Ornithological Society.

Breeding Bird Survey: this survey is a national volunteer project aimed at keeping track of changes in the breeding populations of common bird species in the UK. The survey involves two early morning spring visits to a local, randomly selected, 1-km square to count all the birds you see or hear while walking two 1-km lines across the square. We need skilled volunteers who can identify the birds they are likely to encounter on their square by both sight and sound. For full details, visit the BBS Taking Part pages and contribute to the calculation of bird trends for 117 bird and nine mammal species and help us keep tabs on their population changes.

The BTO/JNCC/RSPB Breeding Bird Survey is a partnership jointly funded by the BTO, RSPB and JNCC, with fieldwork conducted by volunteers. The Breeding Bird Survey (BBS) now incorporates the Waterways Breeding Bird Survey (WBBS).

Hen Harriers breed in Bowland

Hen Harrier has bred in Forest of Bowland, Lancashire, for the first time since 2015.

RSPB wardens discovered two Hen Harrier nests on the United Utilities Bowland Estate in early spring and have been monitoring them closely ever since. The nests were visited recently by the wardens under licence, who were delighted to find four healthy chicks in each of them. A single male harrier has fathered young at both nests and is now regularly taking food to each.

The good news makes a welcome change to the procession of reports of satellite-tagged Hen Harriers either killed or disappearing in unexplained circumstances.

One of this year's Hen Harrier nests in the Forest of Bowland, Lancashire (M Demain).

Hen Harrier remains on the verge of extinction as a breeding bird in England owing to the continuous illegal persecution of the species associated with driven grouse shooting. Although experts estimate there is sufficient habitat for at least 300 pairs across northern England, last year there were only three successful nests in the whole country. Bowland used to be known as England's last remaining stronghold for breeding Hen Harriers, but both 2016 and 2017 proved blank years after just a single chick fledged in 2015.

James Bray, the RSPB's Bowland Project Officer, said: "It is fantastic news that Hen Harriers are breeding once again on the United Utilities Bowland Estate after two barren years. It's an incredibly nerve-wracking time for all involved in protecting these birds, especially for the team that have been constantly monitoring the birds since they arrived on the estate in April. The male Hen Harrier is doing a fantastic job of keeping the chicks in both nests well fed and we're doing all that we can to ensure that they fledge safely."

County Councillor Albert Atkinson, Chairman for the Forest of Bowland AONB Joint Advisory Committee, said: "It is very heartening to hear that Hen Harriers are once again back in the Forest of Bowland and nesting on United Utilities estate. As a Partnership, we are working hard to ensure this iconic bird of Bowland has the best chance of re-establishing as a breeding species in the area."

New generation of cuckoos tagged by BTO

As part of an ongoing study to find out why Common Cuckoo is declining, the British Trust for Ornithology (BTO) has fitted a further 10 individuals with tiny satellite tags this summer.

The study aims to better understand the reasons behind why we have lost almost three-quarters of our Common Cuckoo population over the past 25 years. It has already identified important migration routes via stopover sites in northern Italy and southern Spain, and the precise wintering locations in the Congo rainforest.

Mortality of cuckoos taking the route via Spain has been linked to population decline within the UK. What scientists at the BTO would like to know now is how well our cuckoos make it to and from Africa in different summers, and specifically, how relatively important conditions in the UK and southern Europe are in contributing to a successful – or otherwise – Saharan crossing in autumn.

Male Common Cuckoo (Steve Ashton).

Dr Chris Hewson, lead scientist on the scheme at the BTO, commented: “This has been an incredibly exciting project identifying, for the first time, where our Common Cuckoos go for the winter, how they get there and how survival during migration appears to be contributing to their population decline.

“But we now need to delve a little deeper to see exactly how they interact with their environments along the way. In a wet, cold summer here in the UK, are our cuckoos less likely to successfully get to their wintering grounds? Or are conditions in southern Europe, where the cuckoo make final preparations to cross the Sahara, more important? These are the kind of the questions we would like answers for.”

The first of the satellite-tagged cuckoos could leave at any day now. Each bird has been given a name: Sherwood, Robinson, Knepp, Raymond, Lambert, Carlton II, Sylvester, Thomas, Cameron and Bowie. They were tagged at sites in Suffolk, Sherwood Forest, Thetford Forest, the Knepp Estate in Sussex and the New Forest.

Friday, 8 June 2018

Sunday, 3 June 2018

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)